Benjamin Zephaniah: a Revolutionary Dub Poet [EN]

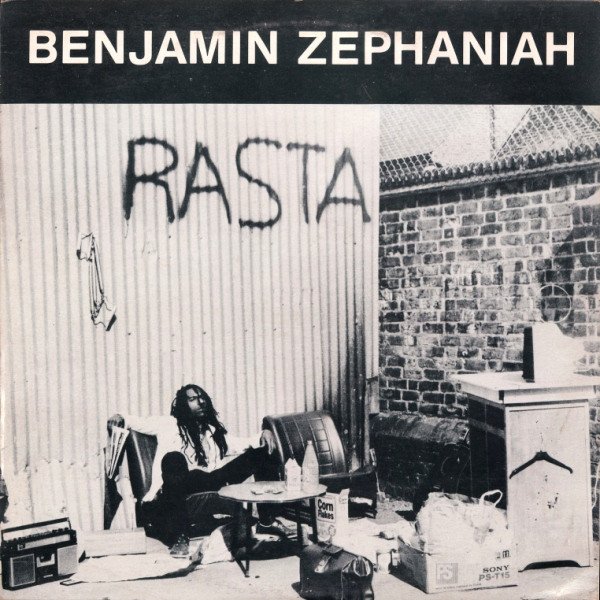

Benjamin Zephaniah is a “poet, writer, lyricist, musician and naughty boy” in his own words. Born in 1958, he lived through years of much racial and social reckoning in the United Kingdom. Born in Birmingham, but having lived in London for many years as a young black man, serving time in prison and being involved in the infamous 1980 race riots, his political and social environment no doubt shaped his outlook early on in his life. It is his sharp social and political observations which inform all of his work, but specifically for this article, his poetry. Writing in Jamaican English, he touches on many themes across his huge canon of material, but most notably it includes politics, racism and anti-racism, reggae, hip hop, the police and police brutality, anarchism, anti-academia and veganism.

In this article we are going to introduce three of his poems that correlate to three of his core themes which particularly resonate with us as a collective. Racism, anti-authoritarianism and veganism. We will also identify a few of the linguistic elements of his work which will hopefully be of interest to our followers who are interested in learning and studying English.

The first poem is called What Stephen Lawrence Has Taught Us. It addresses the racist killing of a young man called Stephen Lawrence in 1993 by a white gang in south London. The very high profile case also highlighted the institutional racism and corruption within the British police. Besides policing and racism (or fascism as is alluded to in the poem) Zephaniah summarises various other important dimensions in this poem. Notably, the institutional squabbling over vocabulary and categorisation while “we continue to die in custody”, the everyday realities of living as a black person in a racially hostile place, the fragility of national identity and corruption. It is a poem that pulls no punches in its deconstruction of what the case says about British society and importantly the power apparatus that enabled it to happen, and sadly continues to happen.

What Stephen Lawrence Has Taught Us

We know who the killers are,

We have watched them strut before us

As proud as sick Mussolinis',

We have watched them strut before us

Compassionless and arrogant,

They paraded before us,

Like angels of death

Protected by the law.

It is now an open secret

Black people do not have

Chips on their shoulders,

They just have injustice on their backs

And justice on their minds,

And now we know that the road to liberty

Is as long as the road from slavery.

The death of Stephen Lawrence

Has taught us to love each other

And never to take the tedious task

Of waiting for a bus for granted.

Watching his parents watching the cover-up

Begs the question

What are the trading standards here?

Why are we paying for a police force

That will not work for us?

The death of Stephen Lawrence

Has taught us

That we cannot let the illusion of freedom

Endow us with a false sense of security as we walk the streets,

The whole world can now watch

The academics and the super cops

Struggling to define institutionalised racism

As we continue to die in custody

As we continue emptying our pockets on the pavements,

And we continue to ask ourselves

Why is it so official

That black people are so often killed

Without killers?

We are not talking about war or revenge

We are not talking about hypothetics or possibilities,

We are talking about where we are now

We are talking about how we live now

In dis state

Under dis flag, (God Save the Queen),

And God save all those black children who want to grow up

And God save all the brothers and sisters

Who like raving,

Because the death of Stephen Lawrence

Has taught us that racism is easy when

You have friends in high places.

And friends in high places

Have no use whatsoever

When they are not your friends.

Dear Mr Condon,

Pop out of Teletubby land,

And visit reality,

Come to an honest place

And get some advice from your neighbours,

Be enlightened by our community,

Neglect your well-paid ignorance

Because

We know who the killers are.

The next poem we are including is called Reggae Head, it critiques and speaks of the wider authoritarianism that is faced by the black community. It was originally a spoken word piece, in the dub poetry tradition, and this is clear in its style of writing. For those who are reading this to study English as a foreign language and to understand its diversity, it is largely written in Jamaican English. That is a variety of English spoken in Jamaica, but also widely spoken in the UK by immigrants from Jamaica to the UK (notably in what is often known as the Windrush Generation) and their descendants. The line repeated at the end of each verse summarises the sentiment of the poem and its defiance in the face of authoritarianism: “Dem can't get de Reggae out me head”. In more standard English, this would be ‘they can’t get the Reggae out of my head’, and could be interpreted as removing or conditioning the blackness out of a black person.

We will briefly explain a few of these linguistic features of Jamaican English for those who are curious about other styles of English and to help the reading of this poem in its original language. ‘Them’, or dem in a Jamaican accent, is often used where standard English would use ‘they’, similarly ‘I’ and ‘me’ are used in the reverse positions. The ‘th’ letter combination is often pronounced as a letter ‘d’, therefore ‘the’ is pronounced as de, ‘they’ as dey, ‘them’ as dem, ‘with’ as wid, ‘that’ as dat, etc. Often the last letters of words will be pronounced very softly, will be modified, or not pronounced at all, for instance ‘just’ is juss, ‘master’ is masta and ‘and’ is an. Other elements include more radical changes like ‘doesn’t’ is often nar. Of course Jamaican English is rich, including many other features typical of linguistic dialects like changes in grammar, word order and different vocabulary. We have just chosen a few examples from this poem to help as an introduction.

Reggae Head

Doctors inject me

Police arrest me

Dem electric shock me

But dat nar stop me,

Oooh

Dem can't get de Reggae out me head.

Dem tek me to a station

Put me on probation,

But I still a dance

Wid de original nation,

Oooh

Dem can't get de Reggae out me head.

Dem sey,

Obey yu masta,

Stop talk Rasta,

But I tek a dub

An juss rock a little fasta,

Noooo

Dem can't get de Reggae out me head.

Dem sey

Bad bowy, stop it,

Dem put money in me pocket

Riddim wise I drop it

An rock it Reggaematic,

Got it

Dem can't get de Reggae out me head.

Dem put

Pill an potions ina me

Dem put

Sum weird notion ina me

Dem put

Fire water ina me

Wan time dem try fe slaughter me,

But I thrive on electricity

Dem tings stimulate I mentally

Now dem calling me de enemy

Cause de reggae roots deep ina me.

Experts debate me

Pop charts

Hate me,

De BNP want to

Annihilate me,

Oooh

Dem can't get de Reggae out me head.

Critics curse

Psychiatrists wail,

Cadburys

Lock me up in jail,

Still

Dem can't get de Reggae out me head.

Computers study me

Commuters worry me

But dem can't hurry me

Or do me injury,

No

Dem can't get de Reggae out me head.

Videos are watching me

But dat is not stopping me

Let dem cum wid dem authority

An dem science and technology,

Oooh

Dem can't get the reggae out my head

The last poem from Benjamin Zephaniah that we want to exhibit is called Talking Turkeys. It is similar to the last poem in that it is also written in Jamaican/spoken English and is also about an important topic, this time veganism. It asks us to “be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas” and not eat them. Zephaniah has often talked about the importance of not eating your “friends” as he refers to turkeys in this poem (but also in other places), and also says he prefers to say that he does not eat animals rather than not eat meat. He says he became a vegan aged 13, and would talk to animals at his all-white school because racism meant he often found himself alone. He clarifies that “amazingly, I never met a racist animal”.

Talking Turkeys

Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas

Cos’ turkeys just wanna hav fun

Turkeys are cool, turkeys are wicked

An every turkey has a Mum.

Be nice to yu turkeys dis christmas,

Don’t eat it, keep it alive,

It could be yu mate, an not on your plate

Say, Yo! Turkey I’m on your side.

I got lots of friends who are turkeys

An all of dem fear christmas time,

Dey wanna enjoy it, dey say humans destroyed it

An humans are out of dere mind,

Yeah, I got lots of friends who are turkeys

Dey all hav a right to a life,

Not to be caged up an genetically made up

By any farmer an his wife.